Gaining Altitude: Airbus A380 to test CFM’s Open-Fan Architecture in Flight

FARNBOROUGH, July 19. With the summer holiday season underway, air travel has bounced back from its lockdown doldrums. But so has the awareness of commercial aviation’s impact on the climate.

Airlines and aircraft and engine manufacturers want to be part of the conversation.

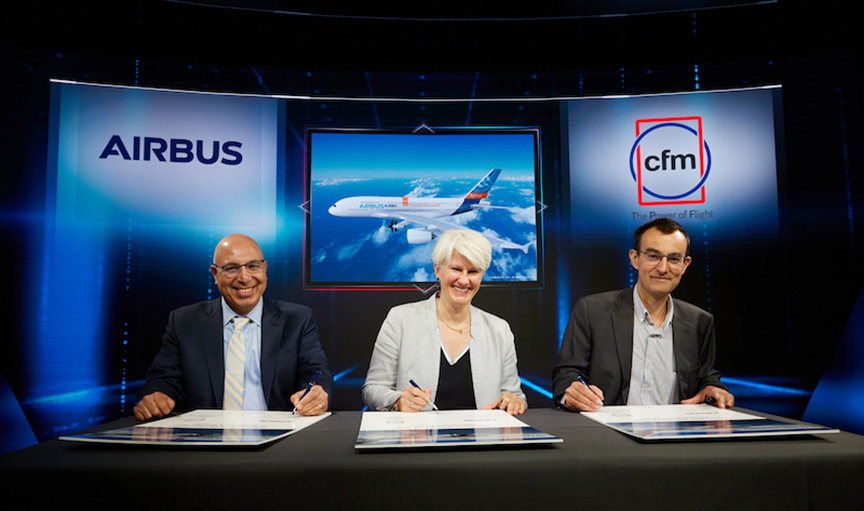

Take Airbus and CFM International, a 50-50 joint company between GE and Safran Aircraft Engines. In February, the two companies announced plans to collaborate on tests of an aircraft engine fueled by hydrogen. And this week at the Farnborough Airshow, Airbus said it would join the cause along with CFM by participating in the RISE (Revolutionary Innovation for Sustainable Engines) Program, launched in 2021. The technology development initiative aims to mature and demonstrate advanced technology that would serve as the foundation for the next-generation CFM engine that will use 20% less fuel and create 20% fewer emissions than the most efficient jet engine in use today and could enter service by the mid-2030s.

In the second half of this decade, the aircraft manufacturer will partner with CFM to carry out a flight test demonstrator program on an Airbus A380 to validate the open-fan engine architecture.

Airbus, CFM, GE and Safran have joined the Air Transport Action Group’s goal to achieve net-zero carbon emissions in aviation by 2050. “We have a vision and commitment to help the industry achieve its net-zero goals,” says Gaël Méheust, president and CEO of CFM International, “and the open-fan flight test demonstration program is an exciting step toward achieving that.”

The fan at the front of this architecture is “open” because, unlike other turbofan engines, it isn’t surrounded by a case. This reduces weight and enables the fan blades to be a good deal larger. As a result, the fan can move much higher volumes of air around the engine, rather than through the engine core.

The difference between these two volumes is called bypass ratio. It’s an important number that describes engine efficiency. CFM engines have grown from an initial bypass ratio of 5:1 in the 1980s to the LEAP engine, which has a bypass ratio of 11:1. An open fan could achieve a bypass ratio above 70:1. And this translates to a 20% reduction in fuel and emissions compared with the most advanced engines flying today. Hybrid electric propulsion and sustainable aviation fuel could lead to even deeper emissions cuts.

CFM has been seeking to build ever more efficient products since the company’s first CFM56 engines entered service in the early 1980s. Since then, its engineers have been able to reduce fuel consumption and CO2 emissions in CFM engines by 40% compared with the engines they replaced.

The news at the Farnborough Airshow represents a homecoming of sorts for the design. The industry started studying the open-fan concept first in the mid-1980s when GE and Safran developed and tested the GE36 engine, also known as the unducted fan engine (UDF). A McDonnell Douglas MD-80 plane powered by a GE36 landed at the Farnborough Airshow in 1988.

The GE36 helped mature key engines technologies such as lighter and stronger fan blades made from carbon-fiber composites.

“That technology was initially tested on the GE36 before making its way onto the GE90 in 1995 and, later, the GEnx and CFM LEAP engine families,” Méheust says.

In 2017, Safran and Avio Aero, a GE Aerospace company, also tested a counter-rotating open-rotor (CROR) engine — which has two rotors spinning in opposite directions — as part of the European Clean Sky sustainability initiative. The work allowed engineers to develop a new, quieter fan configuration.

The RISE open-fan demonstrator engine is being developed with just one large, efficient rotor, spinning at the front of the engine, with a row of stator (stationary) blades just behind.

Since CFM announced the program a year ago, the company has begun successfully testing various components. Ground testing of a fully assembled engine prototype is set to begin around the middle of this decade. Flight testing will take place through the second half of the decade — on GE’s 747 flying test bed in Victorville, California, as well as the A380 flight test program in Toulouse, France.

The aims of the flight demonstrator include gaining insights on how various wing aircraft installation options affect aerodynamic performance. Engineers will look for ways to sharpen the efficiency of the propulsive system, validate the 20% fuel efficiency gains and the improved acoustic models, and ensure compatibility with 100% sustainable aviation fuels.

Hydrogen fuel may also play a part in the eventual final product of the RISE Program, and Airbus is helping out there as well. In February 2022, the two companies announced a joint flight test program to explore ways to use 100% hydrogen, a low-carbon fuel source, to fly a plane.

In addition to the paradigm shift of freeing the fan blades from their housing, other breakthrough technologies, like ceramic matrix composites, are playing a significant role in the RISE Program. Already flying in today’s LEAP engines, this material is one-third the weight of steel but can withstand temperatures as high as 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit, beyond the melting point of many advanced metallic superalloys. That increase in temperature improves an engine’s thermal efficiency. In addition, dozens of other components will be 3D-printed, or additively manufactured, which is faster and less expensive than traditional subtractive methods. This manufacturing technology frees the design space for engineers, enabling them to create more organic designs that are not limited by the capability of machine tools.

For CFM, the program represents a chance to create a generational shift that redefines flight for decades to come. Says Méheust: “It’s all about pushing the technology envelope, redefining the art of the possible, and helping to achieve more sustainable long-term growth for our industry.”