|

Bangalore. India’s space scientists celebrated the birthday of the

country’s first Prime Minister on November 14 in style by landing the Indian national

flag on the moon in a climax to a 22-day mission that galvanized the whole nation.

“It was the most appropriate way to remember Jawaharlal

Nehru,” remarked Gopalan Madhavan Nair, Chairman of the Indian Space Research

Organization (ISRO) in Bangalore. The architect of modern India, Nehru was

the first political leader to realize that India needed science and technology

– including space technology – to emerge from years of colonial rule.  After

circling the moon for six days ISRO’s Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft dropped the

34-kg Moon Impact Probe (MIP) with the orange, white and green Indian flag painted

on its sides – at a place near the moon’s south pole where water, if

present, is most likely to be found (see box). After

circling the moon for six days ISRO’s Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft dropped the

34-kg Moon Impact Probe (MIP) with the orange, white and green Indian flag painted

on its sides – at a place near the moon’s south pole where water, if

present, is most likely to be found (see box).

“We have delivered the

Moon to India,” an exultant Nair, told reporters rather poetically in Bangalore

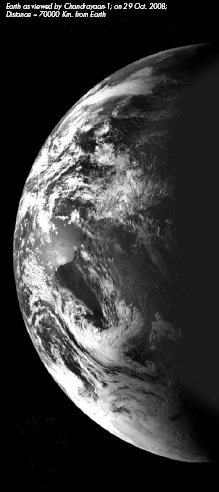

minutes after the probe hit the designated spot on the Moon with calculated precision. Chandrayaan-1’s

nearly 380,000 kilometer journey that began October 22 from the Satish Dhawan

Space Centre in Sriharikota in southern India had gone amazingly well considering

it was the first time that ISRO had sent any object that escaped earth’s

gravity. The thud could not be heard in the rarified atmosphere of the moon.

And because of the light weight of the probe, the plume kicked up by its impact

was too faint to be seen from earth’s observatories. But the message

sent by the impactor was loud and clear: Indian scientists are not just earth-bound

anymore, but are ready to venture into the universe beyond the boundaries of the

planet earth. The successful mission also sent another important message

to the world. It has proved that neither giant rockets nor big budgets are needed

to go to the moon. The rocket that delivered Chandrayaan-1 at the Moon is

a pigmy compared to its giant cousins that the US, Japan and China had used for

such missions. And ISRO's budget for Chandrayaan-1 – about $ 85 million

including $25 million for the ground antenna (see box)— is a fraction of

what Japan spent on its lunar probe Kaguya ($480 million) launched last year,

or what the US has budgeted ($491 million) for its Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

(LRO) to be launched March 2009.  Money

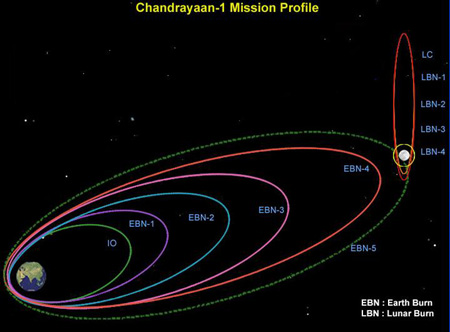

was no problem for ISRO as much as the technical challenges posed by Chandrayaan-1

mission. The real challenge was to choose an ideal trajectory to reach the moon

given the payload limitation of ISRO’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV). Money

was no problem for ISRO as much as the technical challenges posed by Chandrayaan-1

mission. The real challenge was to choose an ideal trajectory to reach the moon

given the payload limitation of ISRO’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV).

The

PSLV had been used to send satellites to low earth orbits but never used for planetary

missions. It is not as powerful as Japan’s H-IIA or China’s Long March-3A

that sent Kaguya and Chang’e-1 to the moon, or the Atlas- 401 that will lift

NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter sometime in March 2009 from Cape Canaveral

in Florida. Significantly, after considering available options ISRO decided

on an elliptical parking orbit around the Earth as the best solution for the Indian

Moon Mission, instead of the traditional “direct transfer” used by all

lunar missions from the 1960s to the 1980s. “Direct transfer would

have required an additional stage to PSLV,” says ISRO scientist V Adimurthy

at the Vikram Space Science Centre where the rocket was built. Therefore

the ISRO team was forced to add more propellants to Chandrayaan-1’s onboard

engine enabling it to reach the lunar orbit on its own thereby avoiding an additional

stage to PSLV. The mission then had both solid and liquid propellants. Development

of the spacecraft bus too posed problems due to space, weight and power constraints,

according to V R Katti of ISRO Satellite Centre (ISAC) in Bangalore where Chandrayaan-1

was assembled and integrated with payloads. The challenge was in accommodating

the 11 different payloads in specific location and orientation in a small spacecraft

of the size of a domestic refrigerator. So, ISRO’s emphasis was on miniaturization

and use of lighter materials. Though a relatively latecomer to the Moon,

India has rightly chosen on its very first mission to focus on Moon’s polar

regions. Most other missions including the Apollo landings had focused on the

equatorial region of moon. Only now has the focus of NASA shifted to the polar

region as a potential place for finding water and setting up a beachhead. ISRO

says that the primary objective of the November 14 landing of the impactor was

to qualify the technologies required for landing Indians on the moon – sometime

possibly around 2015.  With

the crucial phase of the mission now over, the attention of ISRO has now turned

to Chandrayaan-1’s precious cargo – a suite of remaining 10 instruments

from six countries. With

the crucial phase of the mission now over, the attention of ISRO has now turned

to Chandrayaan-1’s precious cargo – a suite of remaining 10 instruments

from six countries.

There were 11 instruments on board: India (5), US (2),

UK (1), Germany (1) Sweden (1) and Bulgaria (1). Of these, the Made in India MIP

now rests on the moon’s surface after sending valuable pictures and data

during its 25 -minute descent. ISRO scientists agree that the real success

of the Chandrayaan-1 mission depends on what data it sends and how it helps to

advance man’s knowledge about the moon. Notably, India’s former

President Dr A P J Abdul Kalam, a space and missile scientist, has suggested that

mankind will have to set up an Earth-Moon-Mars axis to exploit the minerals and

energy resources for the coming generations. Nobody should colonize these but

use them for the mankind. ISRO has dismissed suggestions that India’s

Moon mission was prompted by rivalry with China and that Chandrayaan-1 will repeating

experiments that others have already done. Together, the Indian and foreign

instruments onboard Chandrayaan-1 will explore the moon for the next two years

from a height of 100 kilometers – mapping the minerals, locating water and

imaging the terrain with a high resolution camera that will ultimately yield a

three dimensional atlas of almost the entire moon. (see box) “Chandrayaan-1

carries three instruments that were never before sent by any nation for probing

the Moon or any other planet,” Jitendra Nath Goswami, director of the Physical

Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad and principal scientist for the moon mission

told this writer. (see box) Narendra Bhandari, who was until recently ISRO’s

chief of planetary exploration division, says Chandrayaan-1 will fulfill four

objectives: It will find how volatile elements (specifically water, if it

is there) get transported to the poles from hot lunar surface during the day. We

will have a digital elevation map with 5-meter resolution both on ground and in

elevation, which has not yet been obtained so far. This will enable us to select

potential sites for a future base. We will have chemical and mineral maps

of the Moon. The mineral spectrometer will measure signals up to 3 microns in

the near infrared, not obtained so far, giving us new information about water

and if there are any organic compounds at the poles. Any resources on the

moon can be identified with these chemical and mineral instruments. This

is the first time radar will study the moon. It is capable of seeing below the

surface so we can determine what lies underneath. In fact, if the rest of

the mission is as lucky as it has been till now, Chandrayaan-1 could be the first

to settle the question of whether or not there is water on the Moon. So

far there is no conclusive proof. And it would not be easy to make a firm conclusion

right away. The possibility that ice may be contained in the lunar poles

is inferred from a theory that any water, which did not escape into space, might

have “migrated” to the cold traps in the permanently shadowed polar

regions. A US supplied instrument onboard Chandrayaan-1 will for the first time

verify this concept of “volatiles transport.” (see box) According

to Bhandari, functions of most of the foreign payloads complement those of ISRO’s

instruments especially those that look for water. “Simultaneous photo-geological,

mineralogical, and chemical mapping will enable us to identify different geological

units, which will test the early evolutionary history of the Moon,” he said.

|